Difference between revisions of "Wave Momentum Flux"

| (106 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Ocean Wave Interaction with Ships and Offshore Structures | |

| + | | chapter title = Wave Momentum Flux | ||

| + | | next chapter = [[Wavemaker Theory]] | ||

| + | | previous chapter = [[Wave Energy Density and Flux]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | + | {{incomplete pages}} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Introduction == | |

| − | + | The momentum is important to determine the forces. | |

| − | + | == Momentum flux in potential flow == | |

| − | <center><math> \frac{d\ | + | The momentum flux (the time derivative of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Momentum momentum] <math>\mathcal{M}</math>) is given by |

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}(t)}{\mathrm{d}t} = \rho \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} \iiint_{\Omega(t)} \mathbf{v} \mathrm{d}V | ||

| + | = \rho \iiint_{\Omega(t)} \frac{\partial\mathbf{v}}{\partial t} \mathrm{d}V + \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} \mathbf{v} U_n \mathrm{d}S, | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

| + | where <math> U_n \, </math> is the outward normal velocity of the surface <math> \partial\Omega(t)\, </math>. | ||

| + | This equation follows from the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reynolds_transport_theorem transport theorem]. | ||

| − | So far <math> | + | We begin with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler_equations Euler's equation] in the absence of viscosity |

| + | <center><math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial\mathbf{v}}{\partial t} + (\mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla ) \mathbf{v} = | ||

| + | - \nabla \left(\frac{P}{\rho} + g z\right) | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

| + | where we have defined the direction of gravity to be in the negative <math>z</math> | ||

| + | direction. | ||

| + | We may recast the momentum flux in the form | ||

| + | <center><math> | ||

| + | \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}(t)}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iiint_{\Omega(t)} \left( \nabla ( \frac{P}{\rho} + g z ) + ( \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla ) \mathbf{v} \right) | ||

| + | \mathrm{d}V + \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} \mathbf{v} U_n \mathrm{d}S | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

| + | So far <math> \Omega(t)\, </math> is an arbitrary closed time dependent volume bounded by the time dependent surface <math> \partial\Omega(t)\, </math>. | ||

| + | We have however defined the gravitational acceleration to be in the negative <math>z</math> direction. | ||

| − | + | === Simplification === | |

| − | <center><math> (\ | + | We use the following vector theorem |

| + | <center><math> \nabla \cdot( \mathbf{v} \mathbf{v} )=(\mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla ) \mathbf{v}+ \mathbf{v} (\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v} ) </math></center> | ||

| + | If we have potential flow then <math> \mathbf{v} = \nabla \Phi \,</math> and for solenoidal flow (<math>\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}=0 </math>), we can use Gauss's vector theorem: | ||

| + | <center><math> \iiint_{\Omega(t)} \nabla \cdot( \mathbf{v} \mathbf{v} ) \mathrm{d}V = \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} | ||

| + | \left(\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n} \right) \mathbf{v} \mathrm{d}S </math></center> | ||

| + | In potential flow it follows that | ||

| + | <center><math> \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} ( \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n} ) \mathbf{v} \mathrm{d}S = \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial n} \nabla \Phi \mathrm{d}S | ||

| + | = \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} V_n \mathbf{v} \mathrm{d}S </math></center> | ||

| + | In the above <math> \mathbf{n} \, </math> is the unit vector pointing out of the volume <math> \Omega(t) </math> and <math> V_n = \mathbf{n} \cdot \nabla \Phi </math> | ||

| − | + | Upon substitution in the momentum flux formula, we obtain: | |

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega(t)} \left( ( \frac{P}{\rho} + gz ) \mathbf{n} + \mathbf{v} (V_n - U_n )\right) \mathrm{d}S </math></center> | ||

| − | <center><math> \ | + | This formula is of central importance in potential flow marine hydrodynamics because the rate of change of the linear momentum defined above is just <math> \pm \,</math> the force acting on the fluid volume. When its mean value can be shown to vanish, important force expressions on solid boundaries follow and will be derived in what follows. |

| + | |||

| + | == Hydrostatic Term == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Consider separately the term in the momentum flux expression involving the hydrostatic pressure: | ||

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}_H}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega} gz \mathbf{n}, | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

| + | We break the boundary up into the free surface, ends, body surface, and sea floor at infinite depth, i,.e. | ||

| + | <math>\partial\Omega=\partial\Omega_F + \partial\Omega^{\pm} + \partial\Omega_B + \partial\Omega_{\infty} </math> | ||

| + | The integral over the body surface, assuming a fully submerged body is: | ||

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}_{H,B}}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega_B} gz \mathbf{n} = \rho g V \mathbf{k} </math></center> | ||

| + | where <math>V</math> is the volume. This follows from the vector theorem of Gauss and is the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Displacement_%28fluid%29 principle of Archimedes]. That is, | ||

| + | the momentum flux is equal to the buoyancy force. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We may therefore consider the second part of the integral involving wave effects independently and in the absence of the body, assumed fully submerged. In the case of a surface piercing body and in the fully nonlinear case matters are more complex. Consider the application of the momentum conservation theorem in the case of a submerged or floating body in steep waves. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

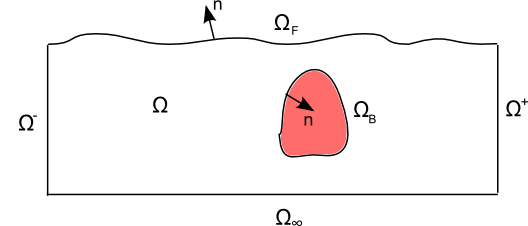

| + | [[Image:Momentum.png|600px|right|thumb|Momentum boundaries]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Here we consider the two-dimensional case in order to present the concepts. Extensions to three dimensions are then trivial. Note that unlike the [[Wave Energy Density and Flux|energy conservation principle]], the momentum conservation theorem derived above is a vector identity with a horizontal and a vertical component. The integral of the hydrostatic term over the remaining surfaces leads to: | ||

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d} \mathcal{M}_{H,S}}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega_F+\partial\Omega^+ + \partial\Omega^- +\partial\Omega_{\infty}} gz \mathbf{n} \mathrm{d}S = - \rho g V_{\text{Fluid}} \mathbf{k} </math></center> | ||

| + | where <math>V_{\mbox{Fluid}} </math> is the fluid volume. | ||

| + | This is simply the static weight of the volume of fluid bounded by <math> \partial\Omega_F, \partial\Omega^+, \partial\Omega^- \,</math> and <math> \partial\Omega_{\infty}.</math> With no waves present, this is simply the weight of the ocean water "column" bounded by <math> \partial\Omega\, </math> which does not concern us here. This weight does not change in principle when waves are present at least when <math> \partial\Omega^+, \partial\Omega^- \,</math> are placed sufficiently far away that the wave amplitude has decreased to zero. So "in principle" this term being of hydrostatic origin may be ignored. However, it is in principle more "rational" to apply the momentum conservation theorem over the "linearized" volume <math> V_L(t) \, </math> which is perfectly possible within the framework derived above. In this case <math> \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}_H}{\mathrm{d}t} \,</math> is exactly equal to the static weight of the water column and can be ignored in the wave-body interaction problem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On <math> S_F; P=P_a=0 \, </math> and hence all terms within the free-surface integral and over <math> S_{\infty} \, </math> (seafloor) can be neglected. It follows that: | ||

| + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d} \mathcal{M}}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \rho \iint_{\partial\Omega^\pm +\partial\Omega_B} \left[ \frac{P}{\rho} \mathbf{n} + \mathbf{v} (V_n -U_n) \right] \mathrm{d}S </math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that the free surface integrals also vanish for the horizontal component since the hydrostatic force is always vertical. This momentum flux formula is of central importance in wave-body interactions and has many important applications, some of which are discussed bellow. Note that the mathematical derivations involved in its proof apply equally when the volume <math> \Omega </math> and its enclosed surface are selected to be at their linearized positions. In such a case it is essential to set <math> U_n=0\,</math> and <math> V_n \ne 0 </math>. Let the math take over and suggest the proper expression for the force. In the fully nonlinear case, <math>U_n \ne 0 \, </math> on <math> \partial\Omega_F\, </math> and <math> P=0 \,</math> on <math> \partial\Omega_F \, </math>! | ||

| + | |||

| + | On a solid boundary: | ||

| + | <center><math> U_n =V_n \,</math></center> | ||

| + | and | ||

| + | <center><math> \overrightarrow{F}_B = \iint_{S_B} P \vec{n} dS </math></center> | ||

| + | With <math> \vec{n} \,</math> pointing inside the body. We may therefore recast the momentum conservation theorem in the form: | ||

| + | <center><math> \overrightarrow{F}_B (t) = - \frac{\mathrm{d} \overrightarrow{M}}{\mathrm{d}t} - \rho \iint_{S^\pm} \left[ \frac{P}{\rho} \vec{n} + \overrightarrow{V} (V_n - U_n) \right] \mathrm{d}S </math></center> | ||

| + | Where <math> S^\pm \, </math> are fluid boundaries at some distance from the body. If the volume of fluid surrounded by the body, free surface and the furfaces <math> S^\pm \, </math> does not grow in time, then the momentum of the enclosed fluid cannot grow either, so <math> \overrightarrow{M}(t) \, </math> is a stationary physical quantity. It is a well known result that the mean value in time of the time derivative of a stationary quantity is zero. So: | ||

| + | <center><math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}\overrightarrow{M}}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = 0 </math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <u> Proof </u>: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}F}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = \lim_{T\to\infty} \frac{1}{2T} \int_{-T}^{T} \frac{\mathrm{d}F{\tau}}{\mathrm{d}\tau} \mathrm{d}\tau = \lim_{T\to\infty} \frac{1}{2T} [F(T) - F(-T) ] </math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math> F(\pm \tau) \, </math> must be bounded for a stationary signal <math> F(t) \, </math>, it follows that <math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}F}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = 0 \, </math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Taking mean values, it follows that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><math> {\overline{\overrightarrow{F}_B (t)}}^t = - \rho \ {\overline{\iint_{S^\pm} \left[ \frac{P}{\rho} \vec{n} + \overrightarrow{V} (V_n - U_n ) \right] \mathrm{d}S}}^t </math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is the fundamental formula underlying the definition of the mean wave drift forces acting on floating bodies. Such forces are very imprtant for stationary floating structures and can be expressed in terms of integrals of wave effects over control surfaces <math> S^\pm \, </math> which may be located at infinity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The extension of the above formula for <math> {\overline{\overrightarrow{F}_B}}^t \, </math> in three dimensions is trivial. Simply replace <math> S^\pm \, </math> by <math> S_{\infty} \, </math>, a control surface at infinity. Common choices are a vertical cylindrical boundary or two vertical planes paraller to the axis of forward motion of a ship. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Applications == | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Mean horizontal momentum flux due to a [[Plane Progressive Regular Waves| Plane Progressive Regular Wave]] === | ||

| + | |||

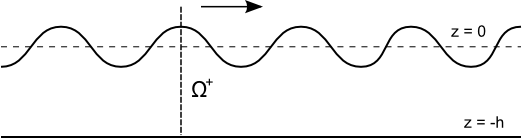

| + | [[Image:Plane_wave_momentum.png|thumb|right|600px|Plane progressive wave momentum]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can determine the mean horizontal momentum flux due to a [[Plane Progressive Regular Waves| Plane Progressive Regular Wave]] with surface displacement | ||

| + | <center><math> \zeta = A \cos (\omega t - k x) \,</math></center> | ||

| + | where <math>\omega</math> and <math>k</math> are related by the [[Dispersion Relation for a Free Surface]] | ||

| + | <math> \omega^2 = gk \tanh kh \, </math> | ||

| − | + | The momentum flux across <math> \Omega^+ \, </math> is given by | |

| − | + | <center><math> \frac{\mathrm{d}M_x}{\mathrm{d}t} = - \int_{-h}^{\zeta} ( P + \rho u^2 ) \mathrm{d}z </math></center> | |

| + | The pressure is given by [[Conservation Laws and Boundary Conditions|Bernoulli's equation]] | ||

| + | <center><math> P = - \rho \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t} - \frac{1}{2} \rho ( u^2 + v^2 ) - \rho g z </math></center> | ||

| + | so that the momentum flux is | ||

| + | <center><math> | ||

| + | \begin{align} | ||

| + | \frac{dM_x}{dt} &= \rho \int_{-h}^{\zeta} \left[ \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t} + \frac{1}{2} ( v^2 - u^2 ) + g z \right] \mathrm{d}z \\ | ||

| + | &= \rho \left( \int_{-h}^{0} + \int_{0}^{\zeta} \right) \left[ \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t} + \frac{1}{2} (v^2 - u^2) + gz \right] \mathrm{d}z | ||

| + | \end{align} | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

| − | + | Taking mean values in time and keeping terms of <math> O(A^2) </math> we obtain: | |

| − | + | <center><math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}M_x}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = {\overline{\rho \zeta(t) \left. \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t} \right |_{h=0}}}^t + \frac{1}{2} \rho \ {\overline{\int_{-h}^{0} (v^2 -u^2 ) \mathrm{d}z}}^t + {\overline{\frac{1}{2} \rho g \zeta^2}}^t </math></center> | |

| − | + | Invoking the [[Linear and Second-Order Wave Theory|linearized dynamic free surface condition]] we obtain | |

| − | + | <center><math> \left. \frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t} \right |_{z=0} = - g \zeta </math></center> | |

| − | + | It follows that: | |

| − | + | <center><math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}M_x}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = {-\frac{1}{2} \rho g \zeta^2 (t)}^t + \frac{1}{2} \rho {\overline{\int_{-h}^0 (v^2-u^2)\mathrm{d}z}}^t </math></center> | |

| − | + | In deep water <math> \overline{v^2} = \overline{u^2} \, </math> and the second term is identically zero, so | |

| + | |||

| + | <center><math> {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}M_x}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = - \frac{1}{2} \rho g {\overline{\zeta^2 (t)}}^t = - \frac{1}{4} \rho g A^2 </math></center> | ||

| − | + | In water of finite depth the wave particle trajectories are elliptical with the mean horizontal velocities larger than the mean vertical velocities. So: | |

| − | <center><math> \ | + | <center><math> \overline{V_H^2} < \overline{U_H^2} </math></center> |

| − | + | Therefore, in finite depth the modulus of the mean momentum flux is higher than in deep water for the same A. | |

| + | So the mean horizontal momentum flux due to a plane progressive wave against its direction of propagation and equal to <math> - \frac{1}{4} \rho g A^2 </math>. | ||

| − | + | === [[Wavemaker Theory]] === | |

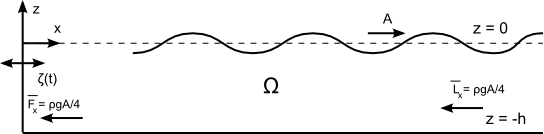

| − | + | [[Image:Wave_maker_momentum.png|600px|right|thumb|Wavemaker momentum]] | |

| + | Consider a wave maker shown in the figure generating a wave of amplitude <math>A</math> at infinity. | ||

| − | + | What is the mean horizontal force on the wavemaker? From the momentum conservation theorem the mean horizontal flux of momentum to the left must flow into the wavemaker. This mean flux translates into a mean horizontal force in the same direction, as shown in the figure. Not an easy conclusion without using some basic fluid mechanics! | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ----- | |

| − | + | This article is based on the MIT open course notes and the original article can be found | |

| + | [http://ocw.mit.edu/NR/rdonlyres/Mechanical-Engineering/2-24Spring-2002/A939D3A9-1F49-46F5-BEB5-0F6646CE340E/0/lecture5.pdf here] | ||

| − | + | [[Ocean Wave Interaction with Ships and Offshore Energy Systems]] | |

Latest revision as of 08:26, 2 January 2019

| Wave and Wave Body Interactions | |

|---|---|

| Current Chapter | Wave Momentum Flux |

| Next Chapter | Wavemaker Theory |

| Previous Chapter | Wave Energy Density and Flux |

Introduction

The momentum is important to determine the forces.

Momentum flux in potential flow

The momentum flux (the time derivative of the momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math]) is given by

where [math]\displaystyle{ U_n \, }[/math] is the outward normal velocity of the surface [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega(t)\, }[/math]. This equation follows from the transport theorem.

We begin with Euler's equation in the absence of viscosity

where we have defined the direction of gravity to be in the negative [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] direction. We may recast the momentum flux in the form

So far [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(t)\, }[/math] is an arbitrary closed time dependent volume bounded by the time dependent surface [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega(t)\, }[/math]. We have however defined the gravitational acceleration to be in the negative [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] direction.

Simplification

We use the following vector theorem

If we have potential flow then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} = \nabla \Phi \, }[/math] and for solenoidal flow ([math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}=0 }[/math]), we can use Gauss's vector theorem:

In potential flow it follows that

In the above [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{n} \, }[/math] is the unit vector pointing out of the volume [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V_n = \mathbf{n} \cdot \nabla \Phi }[/math]

Upon substitution in the momentum flux formula, we obtain:

This formula is of central importance in potential flow marine hydrodynamics because the rate of change of the linear momentum defined above is just [math]\displaystyle{ \pm \, }[/math] the force acting on the fluid volume. When its mean value can be shown to vanish, important force expressions on solid boundaries follow and will be derived in what follows.

Hydrostatic Term

Consider separately the term in the momentum flux expression involving the hydrostatic pressure:

We break the boundary up into the free surface, ends, body surface, and sea floor at infinite depth, i,.e. [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega=\partial\Omega_F + \partial\Omega^{\pm} + \partial\Omega_B + \partial\Omega_{\infty} }[/math] The integral over the body surface, assuming a fully submerged body is:

where [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] is the volume. This follows from the vector theorem of Gauss and is the principle of Archimedes. That is, the momentum flux is equal to the buoyancy force.

We may therefore consider the second part of the integral involving wave effects independently and in the absence of the body, assumed fully submerged. In the case of a surface piercing body and in the fully nonlinear case matters are more complex. Consider the application of the momentum conservation theorem in the case of a submerged or floating body in steep waves.

Here we consider the two-dimensional case in order to present the concepts. Extensions to three dimensions are then trivial. Note that unlike the energy conservation principle, the momentum conservation theorem derived above is a vector identity with a horizontal and a vertical component. The integral of the hydrostatic term over the remaining surfaces leads to:

where [math]\displaystyle{ V_{\mbox{Fluid}} }[/math] is the fluid volume. This is simply the static weight of the volume of fluid bounded by [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega_F, \partial\Omega^+, \partial\Omega^- \, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega_{\infty}. }[/math] With no waves present, this is simply the weight of the ocean water "column" bounded by [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega\, }[/math] which does not concern us here. This weight does not change in principle when waves are present at least when [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega^+, \partial\Omega^- \, }[/math] are placed sufficiently far away that the wave amplitude has decreased to zero. So "in principle" this term being of hydrostatic origin may be ignored. However, it is in principle more "rational" to apply the momentum conservation theorem over the "linearized" volume [math]\displaystyle{ V_L(t) \, }[/math] which is perfectly possible within the framework derived above. In this case [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathcal{M}_H}{\mathrm{d}t} \, }[/math] is exactly equal to the static weight of the water column and can be ignored in the wave-body interaction problem.

On [math]\displaystyle{ S_F; P=P_a=0 \, }[/math] and hence all terms within the free-surface integral and over [math]\displaystyle{ S_{\infty} \, }[/math] (seafloor) can be neglected. It follows that:

Note that the free surface integrals also vanish for the horizontal component since the hydrostatic force is always vertical. This momentum flux formula is of central importance in wave-body interactions and has many important applications, some of which are discussed bellow. Note that the mathematical derivations involved in its proof apply equally when the volume [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] and its enclosed surface are selected to be at their linearized positions. In such a case it is essential to set [math]\displaystyle{ U_n=0\, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V_n \ne 0 }[/math]. Let the math take over and suggest the proper expression for the force. In the fully nonlinear case, [math]\displaystyle{ U_n \ne 0 \, }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega_F\, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ P=0 \, }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ \partial\Omega_F \, }[/math]!

On a solid boundary:

and

With [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{n} \, }[/math] pointing inside the body. We may therefore recast the momentum conservation theorem in the form:

Where [math]\displaystyle{ S^\pm \, }[/math] are fluid boundaries at some distance from the body. If the volume of fluid surrounded by the body, free surface and the furfaces [math]\displaystyle{ S^\pm \, }[/math] does not grow in time, then the momentum of the enclosed fluid cannot grow either, so [math]\displaystyle{ \overrightarrow{M}(t) \, }[/math] is a stationary physical quantity. It is a well known result that the mean value in time of the time derivative of a stationary quantity is zero. So:

Proof :

Since [math]\displaystyle{ F(\pm \tau) \, }[/math] must be bounded for a stationary signal [math]\displaystyle{ F(t) \, }[/math], it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ {\overline{\frac{\mathrm{d}F}{\mathrm{d}t}}}^t = 0 \, }[/math].

Taking mean values, it follows that:

This is the fundamental formula underlying the definition of the mean wave drift forces acting on floating bodies. Such forces are very imprtant for stationary floating structures and can be expressed in terms of integrals of wave effects over control surfaces [math]\displaystyle{ S^\pm \, }[/math] which may be located at infinity.

The extension of the above formula for [math]\displaystyle{ {\overline{\overrightarrow{F}_B}}^t \, }[/math] in three dimensions is trivial. Simply replace [math]\displaystyle{ S^\pm \, }[/math] by [math]\displaystyle{ S_{\infty} \, }[/math], a control surface at infinity. Common choices are a vertical cylindrical boundary or two vertical planes paraller to the axis of forward motion of a ship.

Applications

Mean horizontal momentum flux due to a Plane Progressive Regular Wave

We can determine the mean horizontal momentum flux due to a Plane Progressive Regular Wave with surface displacement

where [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] are related by the Dispersion Relation for a Free Surface [math]\displaystyle{ \omega^2 = gk \tanh kh \, }[/math]

The momentum flux across [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^+ \, }[/math] is given by

The pressure is given by Bernoulli's equation

so that the momentum flux is

Taking mean values in time and keeping terms of [math]\displaystyle{ O(A^2) }[/math] we obtain:

Invoking the linearized dynamic free surface condition we obtain

It follows that:

In deep water [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{v^2} = \overline{u^2} \, }[/math] and the second term is identically zero, so

In water of finite depth the wave particle trajectories are elliptical with the mean horizontal velocities larger than the mean vertical velocities. So:

Therefore, in finite depth the modulus of the mean momentum flux is higher than in deep water for the same A. So the mean horizontal momentum flux due to a plane progressive wave against its direction of propagation and equal to [math]\displaystyle{ - \frac{1}{4} \rho g A^2 }[/math].

Wavemaker Theory

Consider a wave maker shown in the figure generating a wave of amplitude [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] at infinity.

What is the mean horizontal force on the wavemaker? From the momentum conservation theorem the mean horizontal flux of momentum to the left must flow into the wavemaker. This mean flux translates into a mean horizontal force in the same direction, as shown in the figure. Not an easy conclusion without using some basic fluid mechanics!

This article is based on the MIT open course notes and the original article can be found here

Ocean Wave Interaction with Ships and Offshore Energy Systems