Difference between revisions of "Conservation Laws and Boundary Conditions"

| (32 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | + | {{complete pages}} | |

| − | |||

| − | = Coordinate | + | We begin by deriving the equations of motion used to model ocean waves. The equations of motion of a general fluid are given by the celebrated [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navier_Stokes Navier Stokes equations]. However, for the large scale processes that occur in ocean waves many simplifications are possible. |

| + | |||

| + | == Coordinate system and velocity potential == | ||

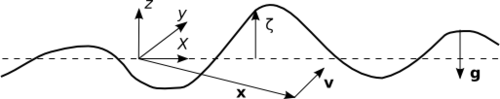

[[Image:Coordinate_system.png|right|thumb|500px|Coordinate System]] | [[Image:Coordinate_system.png|right|thumb|500px|Coordinate System]] | ||

| Line 24: | Line 25: | ||

At the moment we have not yet defined the region of space which is occupied by the fluid. However, the free surface plays a very important role in the propagation of ocean waves. | At the moment we have not yet defined the region of space which is occupied by the fluid. However, the free surface plays a very important role in the propagation of ocean waves. | ||

| − | The most important assumption we make is that the fluid is an [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viscosity ideal fluid]. | + | |

| + | The most important assumption we make is that the fluid is an [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viscosity ideal fluid], i.e. there are no shear stresses due to viscosity and that the flow is [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irrotational irrotational]. This means that | ||

<center><math>\nabla \times \mathbf{v} = 0</math></center> | <center><math>\nabla \times \mathbf{v} = 0</math></center> | ||

| − | We now introduce the very important concept of the velocity potential. Essentially this allows us to express the solution as a function of a scalar (a function which has a single value as opposed to a vector function which has multiple values) rather than a vector | + | We now introduce the very important concept of the velocity potential. Essentially this allows us to express the solution as a function of a scalar (a function which has a single value as opposed to a vector function which has multiple values) rather than a vector throughout the fluid domain. There is an important theorem in vector calculus [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irrotational_vector_field] that if <math>\nabla \times \mathbf{v} = 0</math> then we can express the irrotational vector as the gradient of a scalar function, i.e. |

<center><math> | <center><math> | ||

\mathbf{v} = \nabla \Phi | \mathbf{v} = \nabla \Phi | ||

| Line 34: | Line 36: | ||

where <math>\Phi(\mathbf{x},t)</math> is called the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velocity_potential velocity potential]. | where <math>\Phi(\mathbf{x},t)</math> is called the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velocity_potential velocity potential]. | ||

| − | It turns out that the potential flow model of surface wave propagation and wave-body interactions is very accurate for the kind of length and time scales which are important in the ocean. It is important to realise, however, that we have made considerable simplifications and that certain processes, most notably wave breaking, are in no way covered by this theory. In fact, the process of wave breaking is extremely complicated and is much less well understood | + | It turns out that the potential flow model of surface wave propagation and wave-body interactions is very accurate for the kind of length and time scales which are important in the ocean. It is important to realise, however, that we have made considerable simplifications and that certain processes, most notably wave breaking, are in no way covered by this theory. In fact, the process of wave breaking is extremely complicated and is much less well understood than the potential flow model. |

== Conservation of mass == | == Conservation of mass == | ||

| Line 46: | Line 48: | ||

or | or | ||

<center><math> | <center><math> | ||

| − | \ | + | \partial_x^2 \Phi + \partial_y^2\Phi + \partial_z^2\Phi = 0, |

</math></center> | </math></center> | ||

which is [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplaces_equation Laplace's equation]. | which is [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplaces_equation Laplace's equation]. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 54: | ||

== Conservation of linear momentum == | == Conservation of linear momentum == | ||

| − | We begin with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ | + | We begin with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler_equations_%28fluid_dynamics%29 Euler's equation] in the absence of viscosity |

<center> <math> | <center> <math> | ||

| − | \ | + | \partial_t \mathbf{v} + (\mathbf{v}\cdot \nabla)\mathbf{v}= - \frac1{\rho} \nabla P + \mathbf{g} |

</math> </center> | </math> </center> | ||

where | where | ||

| − | <math> P(\mathbf{ | + | <math> P(\mathbf{x}, t) </math> is the fluid Pressure at <math>(\mathbf{x}, t)</math> and |

<math> \mathbf{g}= - \mathbf{k} g </math> is the acceleration due to gravity where | <math> \mathbf{g}= - \mathbf{k} g </math> is the acceleration due to gravity where | ||

<math> \mathbf{k} </math> is the unit vector pointing in the positive <math>z</math>-direction (so we are now setting the <math>z</math> coordinate to point in the vertical direction). Finally <math> \rho </math> is the water density. | <math> \mathbf{k} </math> is the unit vector pointing in the positive <math>z</math>-direction (so we are now setting the <math>z</math> coordinate to point in the vertical direction). Finally <math> \rho </math> is the water density. | ||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

<center><math> (\mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{v} = \frac 1{2} \nabla (\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{v}) - \mathbf{v}\times ( \nabla \times \mathbf{v}) </math></center> | <center><math> (\mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{v} = \frac 1{2} \nabla (\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{v}) - \mathbf{v}\times ( \nabla \times \mathbf{v}) </math></center> | ||

and since we have irrotational flow (i.e. <math> \nabla \times \mathbf{v}= 0 </math>) Euler's equation becomes | and since we have irrotational flow (i.e. <math> \nabla \times \mathbf{v}= 0 </math>) Euler's equation becomes | ||

| − | <center><math> \ | + | <center><math> \partial_t \mathbf{v} + \frac{1}{2} \nabla (\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{v}) = - \frac 1{\rho} \nabla P - \nabla (g z) </math></center> |

where we have used <math> \nabla z = \mathbf{k} </math>. | where we have used <math> \nabla z = \mathbf{k} </math>. | ||

We now substitute <math> \mathbf{v}= \nabla \Phi </math> and we obtain | We now substitute <math> \mathbf{v}= \nabla \Phi </math> and we obtain | ||

| − | <center><math> \nabla (\ | + | <center><math> \nabla (\partial_t \Phi + \frac{1}{2} \nabla \Phi \cdot \nabla \Phi + \frac {P}{\rho} + g z ) = 0. </math></center> |

We now observe that if | We now observe that if | ||

<center><math> \nabla F( \mathbf{x}, t) =0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad F (\mathbf{x}, t) = C </math></center> | <center><math> \nabla F( \mathbf{x}, t) =0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad F (\mathbf{x}, t) = C </math></center> | ||

where <math> C </math> is an arbitrary constant. | where <math> C </math> is an arbitrary constant. | ||

| − | === Bernoulli's equation === | + | ==== Bernoulli's equation ==== |

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernoulli%27s_equation Bernoulli's equation] follows from the equation above. | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernoulli%27s_equation Bernoulli's equation] follows from the equation above. | ||

| − | <center><math> \ | + | <center><math> \partial_t \Phi + \frac 1{2} \nabla \Phi \cdot \nabla \Phi + \frac {P}{\rho} + g z = C </math></center> |

or | or | ||

| − | <center><math> \frac{P}{\rho} = - \ | + | <center><math> \frac{P}{\rho} = - \partial_t\Phi-\frac{1}{2}\nabla\Phi \cdot \nabla \Phi - g z + C </math></center> |

The value of the constant <math> C </math> is immaterial (it can be thought of as defining the reference pressure. | The value of the constant <math> C </math> is immaterial (it can be thought of as defining the reference pressure. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 87: | ||

In particular, if the particles are modelled as spheres, this equation implies no angular velocity at all times. | In particular, if the particles are modelled as spheres, this equation implies no angular velocity at all times. | ||

| − | = Derivation of | + | == Derivation of nonlinear free-surface condition == |

A very important result is the boundary condition at the free surface of the fluid and air. There are two conditions which relate the free surface displacement <math>\zeta(x,y,t)</math> and the velocity potential <math>\Phi(x,y,z,t)</math> at the free surface. The dynamic condition is derived from the Bernoulli's equation and the kinematic condition is derived from the equations linking the fact that the velocity vector at the surface is given by the gradient of the potential. We will present two methods to derive these equations. | A very important result is the boundary condition at the free surface of the fluid and air. There are two conditions which relate the free surface displacement <math>\zeta(x,y,t)</math> and the velocity potential <math>\Phi(x,y,z,t)</math> at the free surface. The dynamic condition is derived from the Bernoulli's equation and the kinematic condition is derived from the equations linking the fact that the velocity vector at the surface is given by the gradient of the potential. We will present two methods to derive these equations. | ||

| − | == Method I == | + | === Method I === |

We derive the dynamic condition directly from Bernoulli's equation. | We derive the dynamic condition directly from Bernoulli's equation. | ||

On <math> z=\zeta; \ P=P_a \equiv \mbox{Atmospheric Pressure} </math>. | On <math> z=\zeta; \ P=P_a \equiv \mbox{Atmospheric Pressure} </math>. | ||

This allows us to rewrite Bernoulli's equation as | This allows us to rewrite Bernoulli's equation as | ||

| − | <center><math> \frac{P_a}{\rho}=-\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t}-\frac{1}{2}\nabla\Phi\cdot\nabla\Phi-g\zeta+ | + | <center><math> \frac{P_a}{\rho}=-\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial t}-\frac{1}{2}\nabla\Phi\cdot\nabla\Phi-g\zeta+C \qquad \mbox{on} \ z=\zeta(x,y,t) </math></center> |

We will simplify this equation by showing that we are free to set the pressure to any value. | We will simplify this equation by showing that we are free to set the pressure to any value. | ||

| Line 103: | Line 105: | ||

is always zero when tracing a fluid particle on the free surface. So the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_derivative substantial or total derivative] of <math>\tilde{f}</math> must vanish, thus | is always zero when tracing a fluid particle on the free surface. So the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_derivative substantial or total derivative] of <math>\tilde{f}</math> must vanish, thus | ||

| − | <center><math> \frac{D\tilde{f}}{Dt}=0=\left ( \ | + | <center><math> \frac{D\tilde{f}}{Dt}=0=\left (\partial_t + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \right ) \tilde{f}=0, \qquad \mbox{on} \ z=\zeta </math></center> |

| − | Expanding we obtain | + | Expanding, we obtain |

| − | <center><math> \left (\ | + | <center><math> \left (\partial_t + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \right ) (z-\zeta) =0, \qquad \mbox{on} \ z=\zeta </math></center> |

which in turn implies that | which in turn implies that | ||

| − | <center><math> \ | + | <center><math> \partial_t\zeta + \partial_x\Phi \partial_x\zeta + \partial_y\Phi \partial_y\zeta = \partial_z\Phi, \qquad \mbox{on} \ z=\zeta </math></center> |

which is the Kinematic free-surface condition. | which is the Kinematic free-surface condition. | ||

We have already derived the dynamic condtion from Bernoulli's equation | We have already derived the dynamic condtion from Bernoulli's equation | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| − | <math> \ | + | <math> \partial_t\Phi + \frac{1}{2} \nabla \Phi \cdot \nabla \Phi + g \zeta = C - \frac{P_a}{\rho}, \qquad \mbox{on} \ z=\zeta </math></center> |

Constants in Bernoulli's equation may be set equal to zero when we are eventually interested in integrating pressures over closed or open boundaries (floating or submerged bodies) to obtain forces & moments. This follows from a simple application of one of the two Gauss vector theorems. | Constants in Bernoulli's equation may be set equal to zero when we are eventually interested in integrating pressures over closed or open boundaries (floating or submerged bodies) to obtain forces & moments. This follows from a simple application of one of the two Gauss vector theorems. | ||

| − | === Gauss theorem === | + | ==== Gauss theorem ==== |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Force_coordinates2.png|right|thumb|500px|Force coordinates]] |

We need to use the following theorems often called [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gauss_theorem Gauss theorem] although more properly known as the divergence theorem. | We need to use the following theorems often called [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gauss_theorem Gauss theorem] although more properly known as the divergence theorem. | ||

| Line 126: | Line 128: | ||

<math> f(\mathbf{x})</math> is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable scalar function, then | <math> f(\mathbf{x})</math> is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable scalar function, then | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| − | <math> \iiint_{ | + | <math> \iiint_{\Omega} \nabla f \mathrm{d}v = -\iint_{\partial\Omega} f_{s} \mathbf{n} \mathrm{d}s </math> |

</center> | </center> | ||

Note the three scalar identities that follow: | Note the three scalar identities that follow: | ||

| − | <center><math> \iiint_{{ | + | <center><math> |

| − | + | \begin{align} | |

| − | + | \iiint_{{\Omega}} \partial_x f \mathrm{d}v &= - \iint_{\partial\Omega} f n_1 \mathrm{d}s \\ | |

| + | \iiint_{{\Omega}} \partial_y f \mathrm{d}v &= - \iint_{\partial\Omega} f n_2 \mathrm{d}s \\ | ||

| + | \iiint_{{\Omega}} \partial_z f \mathrm{d}v &= - \iint_{\partial\Omega} f n_3 \mathrm{d}s . | ||

| + | \end{align} | ||

| + | </math></center> | ||

The scalar version is as follows where | The scalar version is as follows where | ||

<math> \mathbf{v}</math> is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable vector function | <math> \mathbf{v}</math> is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable vector function | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| − | <math> \iiint_{ | + | <math> \iiint_{\Omega} \nabla \cdot \mathbf{v} = - \iint_{\partial\Omega} \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n} \mathrm{d}s </math></center> |

The scalar identity is often used to prove mass conservation principle. | The scalar identity is often used to prove mass conservation principle. | ||

| − | === Definition of force and moment in terms of fluid pressure | + | ==== Definition of force and moment in terms of fluid pressure ==== |

The force <math>\mathbf{F}</math> is given by | The force <math>\mathbf{F}</math> is given by | ||

<center><math> | <center><math> | ||

| − | \mathbf{F} = \iint_{ | + | \mathbf{F} = \iint_{\partial\Omega} P\mathbf{n}\mathrm{d}s |

</math></center> | </math></center> | ||

where <math>P</math> is the pressure and the moment <math>\mathbf{M}</math> is given by | where <math>P</math> is the pressure and the moment <math>\mathbf{M}</math> is given by | ||

<center><math> | <center><math> | ||

| − | \mathbf{M} = \iint_{ | + | \mathbf{M} = \iint_{\partial\Omega} P(\mathbf{x}\times\mathbf{n})\mathrm{d}s |

</math></center> | </math></center> | ||

| − | It follows from the Gauss theorem that if <math> | + | It follows from the Gauss theorem that if <math> P = C </math> the force and moment over a closed boundary S vanish identically. Hence without loss of generality in the context of wave body interactions we will set <math> C=0 </math>. It follows that the dynamic free surface condition takes the form |

| − | <center><math> \zeta (x,y,t) = - \frac{1}{g} \left \{ \ | + | <center><math> \zeta (x,y,t) = - \frac{1}{g} \left \{ \partial_t\Phi + \frac{1}{2} \nabla\Phi \cdot \nabla\Phi \right \}, \qquad z=\zeta </math></center> |

| − | == Method II == | + | === Method II === |

When tracing a fluid particle on the free surface the hydrodynamic pressure given by Bernoulli (after the constant <math>C</math> has been set equal to zero) must vanish as we follow the particle: | When tracing a fluid particle on the free surface the hydrodynamic pressure given by Bernoulli (after the constant <math>C</math> has been set equal to zero) must vanish as we follow the particle: | ||

| − | <center><math> \frac{D}{Dt} \left \{ \ | + | <center><math> \frac{D}{Dt} \left \{ \partial_t\Phi + \frac{1}{2} \nabla\Phi \cdot \nabla\Phi+gz \right \} =0, \qquad z=\zeta </math></center> |

or | or | ||

| − | <center><math> \left ( \ | + | <center><math> \left ( \partial_t + \mathbf{v} \cdot \nabla \right ) \left ( \partial_t\Phi + \frac{1}{2} \nabla\Phi \cdot \nabla\Phi +gz \right ) =0, \qquad z=\zeta </math></center> |

This condition also follows upon elimination of <math>\zeta</math> from the kinematic & dynamic conditions derived under method I. | This condition also follows upon elimination of <math>\zeta</math> from the kinematic & dynamic conditions derived under method I. | ||

Latest revision as of 11:06, 6 November 2010

| Wave and Wave Body Interactions | |

|---|---|

| Current Chapter | Conservation Laws and Boundary Conditions |

| Next Chapter | Linear and Second-Order Wave Theory |

| Previous Chapter | |

We begin by deriving the equations of motion used to model ocean waves. The equations of motion of a general fluid are given by the celebrated Navier Stokes equations. However, for the large scale processes that occur in ocean waves many simplifications are possible.

Coordinate system and velocity potential

We begin by defining the coordinate system.

At the moment we have not yet defined the region of space which is occupied by the fluid. However, the free surface plays a very important role in the propagation of ocean waves.

The most important assumption we make is that the fluid is an ideal fluid, i.e. there are no shear stresses due to viscosity and that the flow is irrotational. This means that

We now introduce the very important concept of the velocity potential. Essentially this allows us to express the solution as a function of a scalar (a function which has a single value as opposed to a vector function which has multiple values) rather than a vector throughout the fluid domain. There is an important theorem in vector calculus [1] that if [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \times \mathbf{v} = 0 }[/math] then we can express the irrotational vector as the gradient of a scalar function, i.e.

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(\mathbf{x},t) }[/math] is called the velocity potential.

It turns out that the potential flow model of surface wave propagation and wave-body interactions is very accurate for the kind of length and time scales which are important in the ocean. It is important to realise, however, that we have made considerable simplifications and that certain processes, most notably wave breaking, are in no way covered by this theory. In fact, the process of wave breaking is extremely complicated and is much less well understood than the potential flow model.

Conservation of mass

The key equation we will solve to understand ocean waves is Laplace's equation which is derived very simply from the expression for the velocity potential. We assume that the fluid is incompressible so that conservation of mass gives us the following condition

This condition in turn implies, using the definition of the velocity potential that

or

which is Laplace's equation.

Conservation of linear momentum

We begin with Euler's equation in the absence of viscosity

where [math]\displaystyle{ P(\mathbf{x}, t) }[/math] is the fluid Pressure at [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbf{x}, t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{g}= - \mathbf{k} g }[/math] is the acceleration due to gravity where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math] is the unit vector pointing in the positive [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math]-direction (so we are now setting the [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] coordinate to point in the vertical direction). Finally [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is the water density.

We then use the following vector identity

and since we have irrotational flow (i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \times \mathbf{v}= 0 }[/math]) Euler's equation becomes

where we have used [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla z = \mathbf{k} }[/math]. We now substitute [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}= \nabla \Phi }[/math] and we obtain

We now observe that if

where [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is an arbitrary constant.

Bernoulli's equation

Bernoulli's equation follows from the equation above.

or

The value of the constant [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is immaterial (it can be thought of as defining the reference pressure. It is also worth noting that the angular momentum conservation principle is contained in [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla \times \mathbf{v} = 0. }[/math] In particular, if the particles are modelled as spheres, this equation implies no angular velocity at all times.

Derivation of nonlinear free-surface condition

A very important result is the boundary condition at the free surface of the fluid and air. There are two conditions which relate the free surface displacement [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta(x,y,t) }[/math] and the velocity potential [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(x,y,z,t) }[/math] at the free surface. The dynamic condition is derived from the Bernoulli's equation and the kinematic condition is derived from the equations linking the fact that the velocity vector at the surface is given by the gradient of the potential. We will present two methods to derive these equations.

Method I

We derive the dynamic condition directly from Bernoulli's equation. On [math]\displaystyle{ z=\zeta; \ P=P_a \equiv \mbox{Atmospheric Pressure} }[/math]. This allows us to rewrite Bernoulli's equation as

We will simplify this equation by showing that we are free to set the pressure to any value.

The kinematic condition is derived as follows. On [math]\displaystyle{ z=\zeta }[/math] The mathematical function

is always zero when tracing a fluid particle on the free surface. So the substantial or total derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{f} }[/math] must vanish, thus

Expanding, we obtain

which in turn implies that

which is the Kinematic free-surface condition.

We have already derived the dynamic condtion from Bernoulli's equation

Constants in Bernoulli's equation may be set equal to zero when we are eventually interested in integrating pressures over closed or open boundaries (floating or submerged bodies) to obtain forces & moments. This follows from a simple application of one of the two Gauss vector theorems.

Gauss theorem

We need to use the following theorems often called Gauss theorem although more properly known as the divergence theorem. We begin with the vector version. If [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{n} }[/math] is the unit normal vector pointing inside the volume [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] with surface [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(\mathbf{x}) }[/math] is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable scalar function, then

[math]\displaystyle{ \iiint_{\Omega} \nabla f \mathrm{d}v = -\iint_{\partial\Omega} f_{s} \mathbf{n} \mathrm{d}s }[/math]

Note the three scalar identities that follow:

The scalar version is as follows where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] is an arbitrary sufficiently differentiable vector function

The scalar identity is often used to prove mass conservation principle.

Definition of force and moment in terms of fluid pressure

The force [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} }[/math] is given by

where [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is the pressure and the moment [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{M} }[/math] is given by

It follows from the Gauss theorem that if [math]\displaystyle{ P = C }[/math] the force and moment over a closed boundary S vanish identically. Hence without loss of generality in the context of wave body interactions we will set [math]\displaystyle{ C=0 }[/math]. It follows that the dynamic free surface condition takes the form

Method II

When tracing a fluid particle on the free surface the hydrodynamic pressure given by Bernoulli (after the constant [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] has been set equal to zero) must vanish as we follow the particle:

or

This condition also follows upon elimination of [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math] from the kinematic & dynamic conditions derived under method I.

This article is based on the MIT open course notes and the original article can be found here